The removal of caffeine is something most coffee drinkers

would scoff at, however for someone that likes to drink the beverage for the

taste, and not the caffeine, finding a good decaf is a never-ending journey.

But before I answer how come it’s so hard to find a good

decaf, how does the coffee become decaffeinated in the first place?

It starts with dissolving the caffeine out by some solvent,

or other compound.

This can be done is range of ways and is designed to minimise

the amount of flavour compounds that are dissolved with the caffeine.

Firstly, this can be done by chemical solvents that

selectively dissolve caffeine. The original solvent being Benzene, a known

carcinogen, which we have gladly moved on from to methylene chloride, approved

by the FDA, and ethyl acetate, which occurs naturally in trace amounts in

ripening fruit. Even if some of these solvents remain in the beans, they are

very volatile and so when the beans are exposed to heat in the roasting process

and finally the brewing, it is very unlikely these solvents will still be in

the beans and therefore in your cup of coffee.

Indirectly-dissolved

The beans are soaked in hot water, and then is water is

added to the solvent which bonds to the caffeine, before the mixture is heated,

and the solvent and caffeine is evaporated. The remaining water is then added

back to the beans and so the oils and flavouring compounds are reabsorbed the

beans.

Directly-dissolved

The beans are first steamed, to open their pores for better

absorption of the solvent. Then they are rinsed repeatedly for 10 hours with

the solvent to remove the caffeine, before being steamed again to evaporate the

remaining solvent.

The beans can also be treated by other substances that act

to dissolve the caffeine that aren’t classified as “chemicals”.

Swiss-Water Process:

First the beans are soaked in hot water to dissolve the

caffeine, and this water in then passed through an activated charcoal filter,

which allow smaller molecules like oils and flavour compounds to pass through

and blocks larger caffeine molecules.

This first batch of beans is entirely caffeine free, but

also flavourless, but you are left with the water that is saturated with

dissolved flavour compounds.

Another batch of coffee beans is then able to be dissolved

with the previous water. Since this water is saturated with flavouring

compounds, no more can dissolve, but the caffeine in the new batch of beans is

able to be dissolved, and then removed via the activated carbon filter.

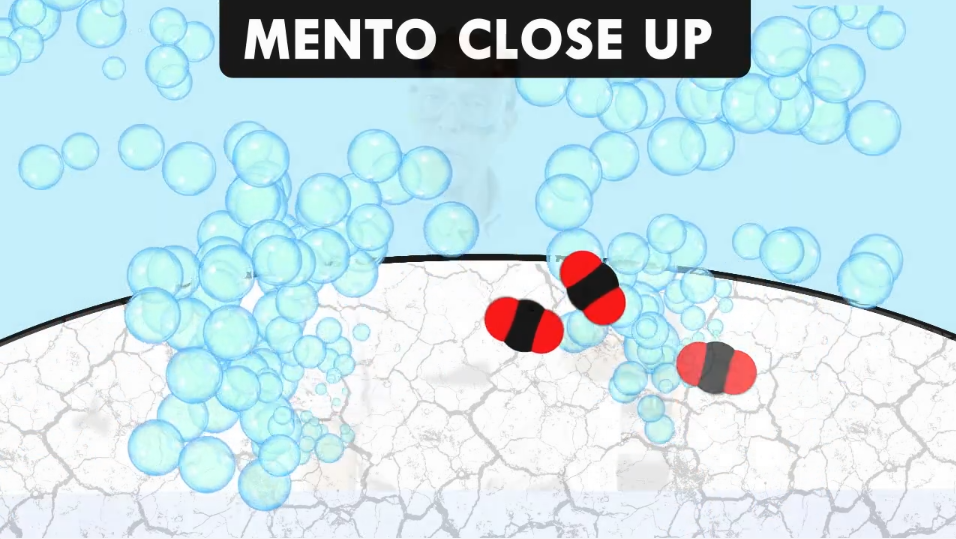

Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Method:

This method is the mostly recently developed and utilises

carbon dioxide to selectively dissolve the caffeine in the coffee beans.

Water soaked beans are placed into an extraction vessel,

which is pressurised and sealed, to create the conditions for Co2 to be in its

liquid phase and dissolve the caffeine. The CO2 is then transferred to the

absorption chamber where the pressure is released, and CO2 returns to its

gaseous state, and the caffeine is left behind. This allows the CO2 to be

recycled and decaffeinate another batch of coffee beans.

Many problems that arise from these methods is the use of

heat and loss in moisture content.

As we know that heat

can denature proteins and break bonds in compounds, so heat treating the coffee

beans, in addition to roasting and making the coffee, can compromises the

flavour compounds in the coffee.

Decaffeinating the coffee beans also reduces their moisture

content, and browns them, which means they roast faster, but also lack the

visual indicator of how roasted the bean is as compared to caffeinated beans

which are green before the roasting process.

These factors mean it is more likely your cup of decaf is

over-roasted and has that burnt flavour that we all hate, as well as less favourable

than your regular cup.

Referenced from https://coffeeconfidential.org/health/decaffeination/

and Chem 120 Section One Content: application of CO2 as a supercritical fluid.